New Outlooks on Internationalizing Higher Education: Business School Trends

It is generally assumed that business schools and programs should be especially receptive to internationalization initiatives. Business is, after all, frequently counted as a leading force in globalization or a field of practice highly subject to its effects. The present article reviews some of the recent literature on the subject from sources such as the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AASCB), a main international accreditation body, as well as the work of diverse scholars. These tend to show that internationalization is indeed a topic of great interest among business school leaders, if the pace of change has not yet met with the satisfaction of all.

As indicated above, the desirability of internationalizing business education appears self-evident. ‘Businesses today,’ write for example the authors of one recent work, ‘operate in a new, competitive global economy with a pace of change that is accelerated by technology’. Students must therefore ‘learn to adapt to a wide variety of local, national, and regional rules, regulations, institutions, business practices, and social norms’ (Kedia and Englis, 15). These concerns touch upon virtually every facet of an enterprise’s operation, as indicated for example by a recent article on accounting education. According to the authors, ‘as accounting frameworks converge with International Financial Reporting Standards and audits of international organizations become more common, it is imperative that accounting students also learn more about the global business environment in which they will participate’ (Meier and Smith, 35).

In sum, ‘business schools need to be more global,’ urges Andrew J. Policano, Chairman of AACSB International and Dean of The Paul Merage School of Business at the University of California, Irvine. ‘They depend on ‘‘selling their products’’ to an increasingly global market that demands students who are prepared to implement global strategy and who possess international experience, cultural awareness, and the ability to work in cross-cultural environments’ (AACSB 2011, xi). The AASCB has accordingly published new accreditation standards which incorporate these aims. For example, schools are now expected to demonstrate that their curriculum ‘fosters sensitivity toward and greater understanding and acceptance of cultural differences and global perspectives.’ The guidelines further state that ‘graduates should be prepared to pursue business or management careers in a diverse global context’ and that ‘students should be exposed to cultural practices different than their own’ (AACSB 2013, 7).

The remarks cited above from AACSB Chairman Policano are taken from the Foreword of a 2011 report issued by the organization on Globalization of Management Education: Changing International Structures, Adaptive Strategies, and the Impact on Institutions. This document – a hefty work of some 350 pages – represents one of the more extensive reviews of business school internationalization efforts to date. The authors begin by noting that ‘at no other point in history have business schools invested so much energy into seeking new means of expanding their international networks, incorporating international perspectives into learning experiences and faculty research, and establishing (or maintaining) a globally recognized brand’ (AACSB 2011, xi). They were nevertheless forced to add that ‘large gaps remain in our knowledge about the globalization of management education: scale, scope, curriculum, modes of collaboration, and impact’ (Ibid). Still greater reservations were expressed on the subject of the quality of student learning experiences. ‘Unfortunately,’ they observe on this count:

… present efforts by business schools to globalize typically include a series of independent and fragmented activities. These activities are mostly focused on student and/or faculty diversity and the establishment of cross-border partnerships for student exchange. The Task Force is concerned that business schools are not responding to globalization in a coherent way, i.e., they tend to focus on collecting an array of activities (e.g., exchange programs) with insufficient emphasis on learning experiences and intended outcomes (Ibid, 4-5).

The causes of and possible remedies for these shortcomings are discussed later in the report, with particular stress placed on matters of curriculum design. Endeavors in this vein, in contrast for example to grander undertakings such as the opening of branch campuses, are viewed as especially important as they lie within reach of all institutions, great and small (Ibid, 110). Curriculum reform is furthermore an area of action, they find, that is supported by deans and others in leadership positions. In fact, their ‘motivational’ concerns are directed toward faculty, for whom ‘the efforts seem not to have passed the cost-benefit tests of personal involvement’ -- an issue that has been raised in previous AHEA research reviews (Ibid, 112).

The AACSB report cites finally ‘structural’ and ‘cognitive’ barriers to internationalization. In the case of the former, reference is made to traditions and cultural dispositions which ‘reinforce a domestic focus’ (Ibid, 113). By ‘cognitive barriers,’ the authors refer in turn to a prevalent ‘under-adaptation to international differences’, as manifested in curricula which are ‘prone to overestimate levels of cross-border integration’ (Ibid, 114). This can even arise in schools which have international branch campuses: Although highly internationalized from a structural standpoint, these institutions may yet be prone ‘to pursue a degree of universalization across space… by propagating curricula that are developed domestically across national borders.’ But ‘if differences are large,’ they continue, ‘this is a recipe for stretching domestic content past its point of applicability’ (114-115).

The preceding sections have focused on curriculum revision, but student and faculty mobility are also considered critical components of business education internationalization. Faculty mobility is for example well represented in programming initiatives at the Centers for International Business and Research [CIBER centers were founded in 1988 by the Department of Education to promote international business education; they are located in 15 universities across the United States]. In the case of student mobility, this remains for many a premier means for achieving the practical knowledge and intercultural competence articulated in the AASCB standards (see for example Black and Duhon; Heischmidt; Tuleja). Still other scholars cite a considerable body of studies which ‘suggest that employers regard study abroad favorably and believe study abroad experiences develop highly-desirable skills for career advancement’ (Orahood et al, 118).

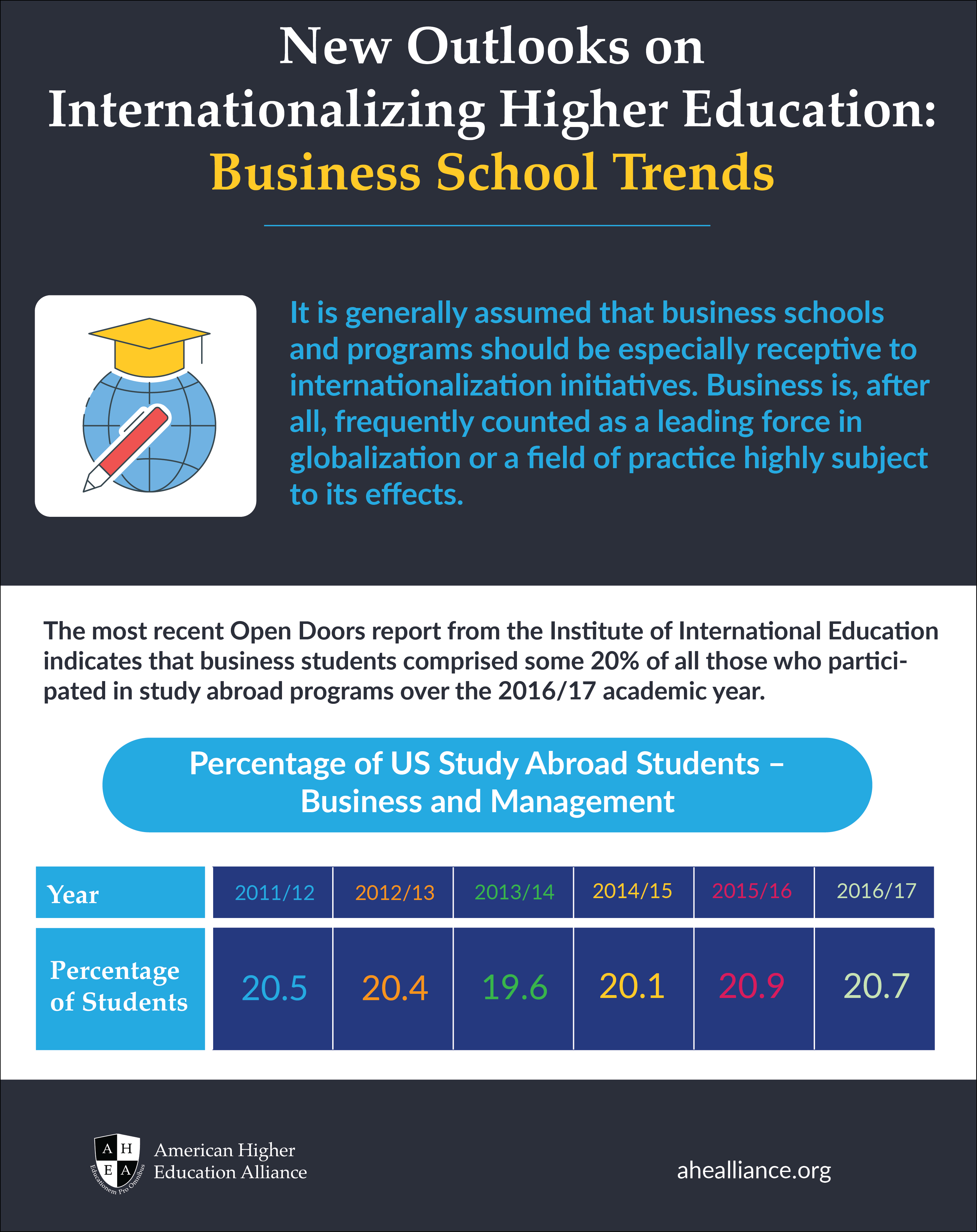

In terms of numbers, the most recent Open Doors report from the Institute of International Education (see below) indicates that business students comprised some 20% of all those who participated in study abroad programs over the 2016/17 academic year. This compares favorably with participation rates from other fields. In fact, the business student share of total study abroad participation is only surpassed by STEM students (26%) – an IIE category which encompasses five major disciplines (Physical/Life Sciences, Health Professions, Engineering, Math/Computer Science, and Agriculture). That said, the rate of participation of business students in mobility programming has remained unchanged over the period, as compared again with STEM, which has shown a steady rise in share since 2006/07 when it accounted for 17.5% of study abroad students.

The literature and data reviewed above tend to confirm the general view that internationalization is a subject of serious consideration for business school leaders and accreditation organizations. Business schools may in sum be held to occupy a place on the leading edge of internationalization efforts to date, if considerable potential for innovation and growth remains. The works cited above have touched upon a number of issues and challenges in this vein, such as curriculum reform and faculty engagement, that have surfaced in previous AHEA reviews and are indeed common to internationalization efforts across a wide range of disciplines.

-----Work Cited-----

AACSB International, 2013 Eligibility Procedures and Accreditation Standards for Business Accreditation [revised July 1, 2018].

AACSB International, Globalization of Management Education: Changing International Structures, Adaptive Strategies, and the Impact on Institutions. Report of the AACSB International Globalization of Management Education Task Force (2011).

Black, H. Tyrone, and David L. Duhon. Assessing the impact of business study abroad programs on cultural awareness and personal development’, Journal of Education for Business 81, 3 (2006): 140-144.

Heischmidt, Kenneth. "Strategic and Operational Planning: Impacting Results in International Business Study Programs." Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice 18, no. 1 (2018): 92-102.

Kedia, Ben L., and Paula D. Englis. ‘Internationalizing Business Education for Globally Competent Managers’, Journal of Teaching in International Business 22, 1 (2011): 13-28.

Meier, Heidi Hylton, and Deborah Drummond Smith. ‘Achieving globalization of AACSB accounting programs with faculty-led study abroad education’, Accounting Education 25, no. 1 (2016): 35-56.

Orahood, Tammy, Larisa Kruze, and Denise Easley Pearson. "The Impact of Study Abroad on Business Students' Career Goals." Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad 10 (2004): 117-130.

Tuleja, Elizabeth A. "Developing cultural intelligence for global leadership through mindfulness." Journal of Teaching in International Business 25, no. 1 (2014): 5-24.