New Outlooks on Internationalizing Higher Education: Community Colleges

Previous articles in this series have cited research from the American Council of Education (ACE) and other organizations which indicate the leading part played by large universities and private liberal arts colleges in higher education internationalization. According for example to the ACE’s Mapping Internationalization reports and data from the IEE’s Open Doors project, institutions of this kind stand out as being far ahead in a number of important categories, from the proportion of their students who participate in mobility programs and international student recruitment, to the expansion of co-curricular activities. That said, a considerable amount of new research is being conducted on the state of internationalization efforts in other sectors. Scholars appear to be particularly interested in what is happening at American community colleges.

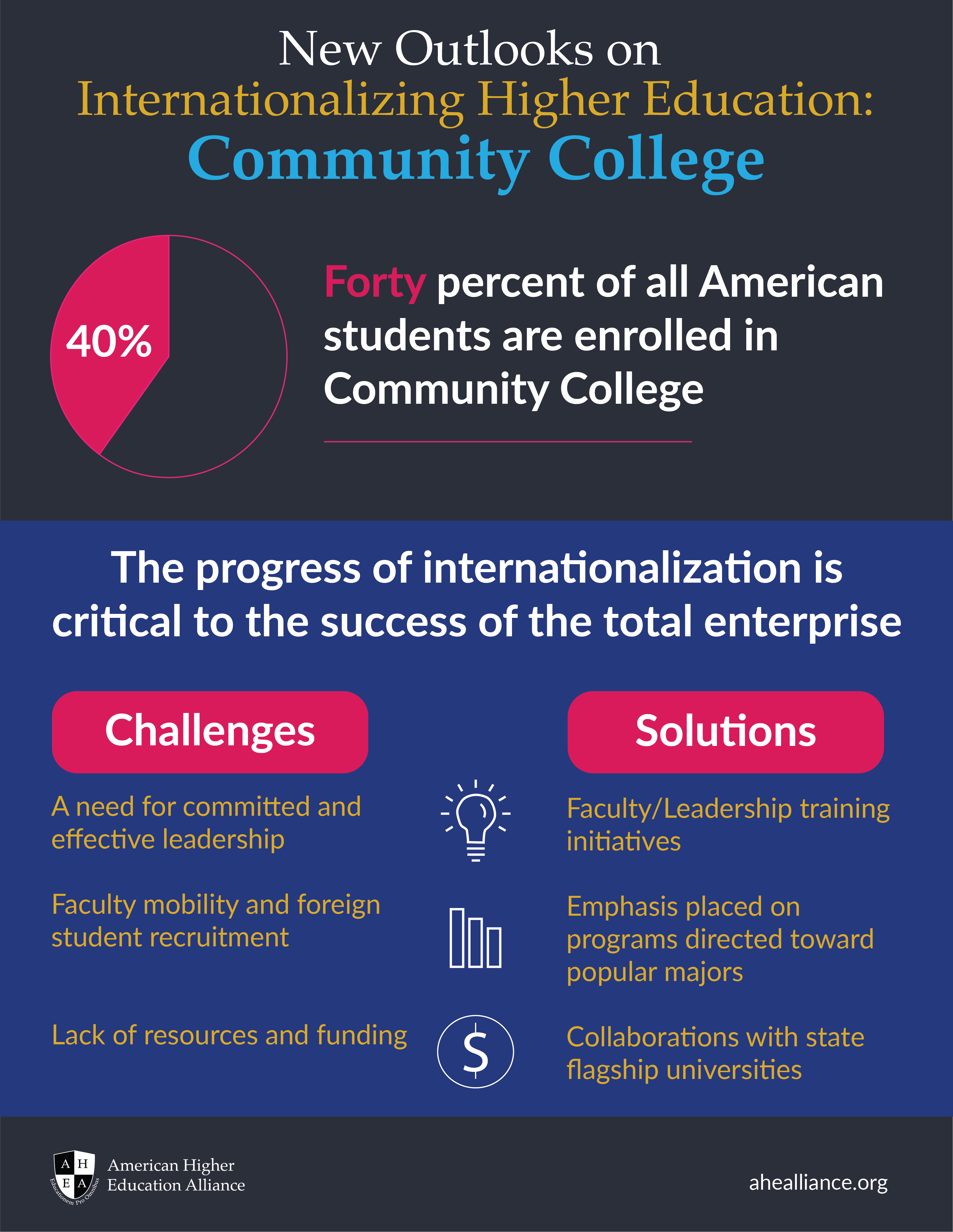

Given that some forty percent of American students are enrolled in community colleges, the progress of internationalization efforts in this sector seems critical to the success of the total enterprise. Growing recognition of this fact is evidenced by documents such as the Joint Statement on the Role of Community Colleges in International Education (2006) issued by the American Association of Community Colleges and the Association of Community College Trustees. According to the Joint Statement: ‘Community college leaders—their governing boards and the chief executives that lead them, as well as their administrators, faculty, and staff who oversee programs and services—have an obligation not only to embrace global education, but to engage their communities in understanding its importance’ (AACC and ACCT). The authors of the Joint Statement call in turn for a host of familiar initiatives intended to meet these aims, including greater curricular emphasis on the study of foreign languages and cultures, the expansion of student and faculty mobility programs, and an increase in the recruitment of foreign students.

As recognition of the importance of community colleges to the internationalization of American higher education grows, attention has naturally turned to the challenge of putting such ideals into practice. For some scholars, the hurdles faced by community colleges are not distinct from those confronting institutions in other sectors. Madeline Green for example writes that the ‘ACE’s work with all types of higher education institutions suggests that the barriers to internationalization are not sector-specific. Thus community colleges experience the same obstacles as other institutions, and the differences are usually a matter of degree’ (Green, 18). Ranking high in Green’s list of these universal challenges is the need for committed and effective leadership. ‘Not surprisingly,’ she writes, ‘the institutions that are most successful in internationalization have presidents and chief academic officers who are ardent supporters and public champions of internationalization’ (Green, 22). These claims are borne out, or so some studies indicate, by the success of those community colleges whose leaderships arrived at an early recognition of the value of internationalization and acted accordingly (Bermingham and Ryan).

Leadership issues have also been the focal point of several works by Rosalind Raby, who, with co-author Edward Valeau, has argued in one recent piece that the inadequacy of efforts on the internationalization front stems from the entrenched belief that ‘serving the local community is the opposite of a global connection.’ As a result of these conventions and traditions, they continue, ‘internationalization is not included in community college training programs… is not a component of budget and finance discussions… and is not institutionalized in strategic planning or college level action items (Raby and Valeau, 10). For Opp and Gosetti, echoing points made here and by scholars in previous AHEA research reviews, these issues can in part be addressed by requiring that international work experience and interests be included in the recruitment and performance reviews of chief executive, academic, and student affairs officers (Opp and Gosetti, 69-70).

The works cited above tend to suggest that the challenges to internationalization faced by community colleges are not entirely different from those confronted by other institutions and that, like these, progress depends greatly on the attitude of senior leadership. However, readers will also find a somewhat different point of view conveyed in other works on the subject which indeed argue that community colleges face a unique set of obstacles. On one hand, there is the often-cited issue of resources. As Opp and Gosetti write, community college internationalization endeavors in the areas of faculty mobility and the recruitment of foreign students (as well as the availability of resources necessary to serve them) are hampered by a prevalent ‘lack of adequate funding’ (Opp and Gosetti, 72). This issue is also acknowledged to some degree by Madeline Green who writes that ‘The problem of insufficient resources exists on nearly every community college campus and is the most frequently cited barrier to change’ (Green, 20).

Other works of this kind focus on student issues and concerns. For example, the low participation rate of community college students in mobility programs can be directly attributed, write the authors of another recent study, to the ‘distinct characteristics and needs of the typical community college student demographic’ (Bartzis et al, 237). They continue:

Characteristically, community college students are engaged in degree programs which are brief, sequentially organized with regard to curriculum, and structured with little room for activities that may not satisfy (or appear to satisfy) specific degree requirements. They frequently maintain one or more jobs while attending college, a fact which prevents them from being able to leave the country for extended periods of time. Many community college students are financially challenged and the expense of study abroad is a real or perceived barrier (Bartzis et al, 238).

If the challenges described above appear daunting, there is nevertheless a growing body of case studies which depict how schools throughout the country have sought to overcome them. Bartzis and his co-authors describe for example the experiences of Harper College and Fox Valley Technical College in Indiana and Wisconsin, respectively. In the case of the former, the authors give particular attention to Harper’s establishment of the Global Focus initiative, a classic internationalization at home venture which seeks to ‘infuse’ the curriculum with ‘global content’. This is a faculty-directed and led internationalization initiative involving a considerable amount of training in fashioning global learning outcomes and assessment practices (Bartzis et al, 241). In the case of Fox Valley Technical College, the authors describe the creation of ‘an international field study program, which speaks to the distinct needs and circumstances of its unique student body’ (Bartzis et al, 242). Emphasis is thus placed on the development of mobility programs that are typically of short duration and directed toward popular majors, such as health care or business.

Additional internationalization opportunities for community colleges may lie in the adoption of what Opp and Gosetti refer to as a ‘regional approach to internationalization’ (Opp and Gosetti, 73). They allude here to collaborations between community colleges and state flagship universities, especially in areas such as international student recruitment, that may address some of the funding challenges cited above. Community college leaders might therefore ‘work with neighboring four-year colleges to recruit students to both institutions’, as witnessed in the relationship the authors describe between Kirkland Community College and the University of Iowa. Katherine Cierniak and Anne Maree Ruddy cite another example of such a partnership in the form of the Global Learning Across Indiana initiative, which promotes collaboration and resource-sharing on internationalization initiatives between the state’s flagship university and its community college system (Cierniak and Ruddy).

In sum, as Opp and Gosetti report, a movement is clearly underway to ‘internationalize the experience’ of American community college students (Opp and Gosetti, 67). The literature cited above, which of course represents only a small portion of that available on the subject, indicates what community colleges have in common with other types of institutions embarked on such an enterprise, as well as some challenges unique -- or at least especially common – to their sector of the American higher education landscape. It further indicates some important new ideas, such as cross-sector collaboration and faculty/leadership training initiatives, that are being developed to meet these challenges and worthy of greater consideration in the future.

-----------------------------------------

Works Cited

American Association of Community Colleges and Association of Community College

Trustees. Building the Global Community: A joint Statement on the Role of Community Colleges in International Education (Washington, D.C.: American Association of Community Colleges, 2006).

Bartzis, Opal Leeman, Kelly J. Kirkwood, and Thalia M. Mulvihill. ‘Innovative Approaches to Study Abroad at Harper College and Fox Valley Technical College’, in Raby and Valeau, eds., International Education at Community Colleges, pp. 237-246.

Bermingham, Jack, and Margaret Ryan. ‘Transforming International Education through Institutional Capacity Building’, New Directions for Community Colleges, 161 (2013), pp. 55-70.

Cierniak, Katherine, and Anne-Maree Ruddy. ‘Partnering for New Possibilities: The Development of a Global Learning Certificate’, in Raby and Valeau, eds., International Education at Community Colleges, pp. 247-262.

Green, Madeleine F. ‘Internationalizing Community Colleges: Barriers and Strategies’, New Directions for Community Colleges, 138 (2007), pp. 15-24.

Opp, Ronald D., and Penny Poplin Gosetti. ‘The Role of Key Administrators in Internationalizing the Community College Student Experience’, New Directions for Community Colleges, 165 (2014), pp. 67-75.

Raby, Rosalind Latiner, and Edward J. Valeau. ‘Global Is Not the Opposite of Local: Advocacy for Community College International Education’, in Raby and Valeau, eds., International Education at Community Colleges, pp. 9-22.

Raby, Rosalind Latiner, and Edward J. Valeau, eds. International Education at Community Colleges: Themes, Practices, and Case Studies (New York: Palgrave, 2016).