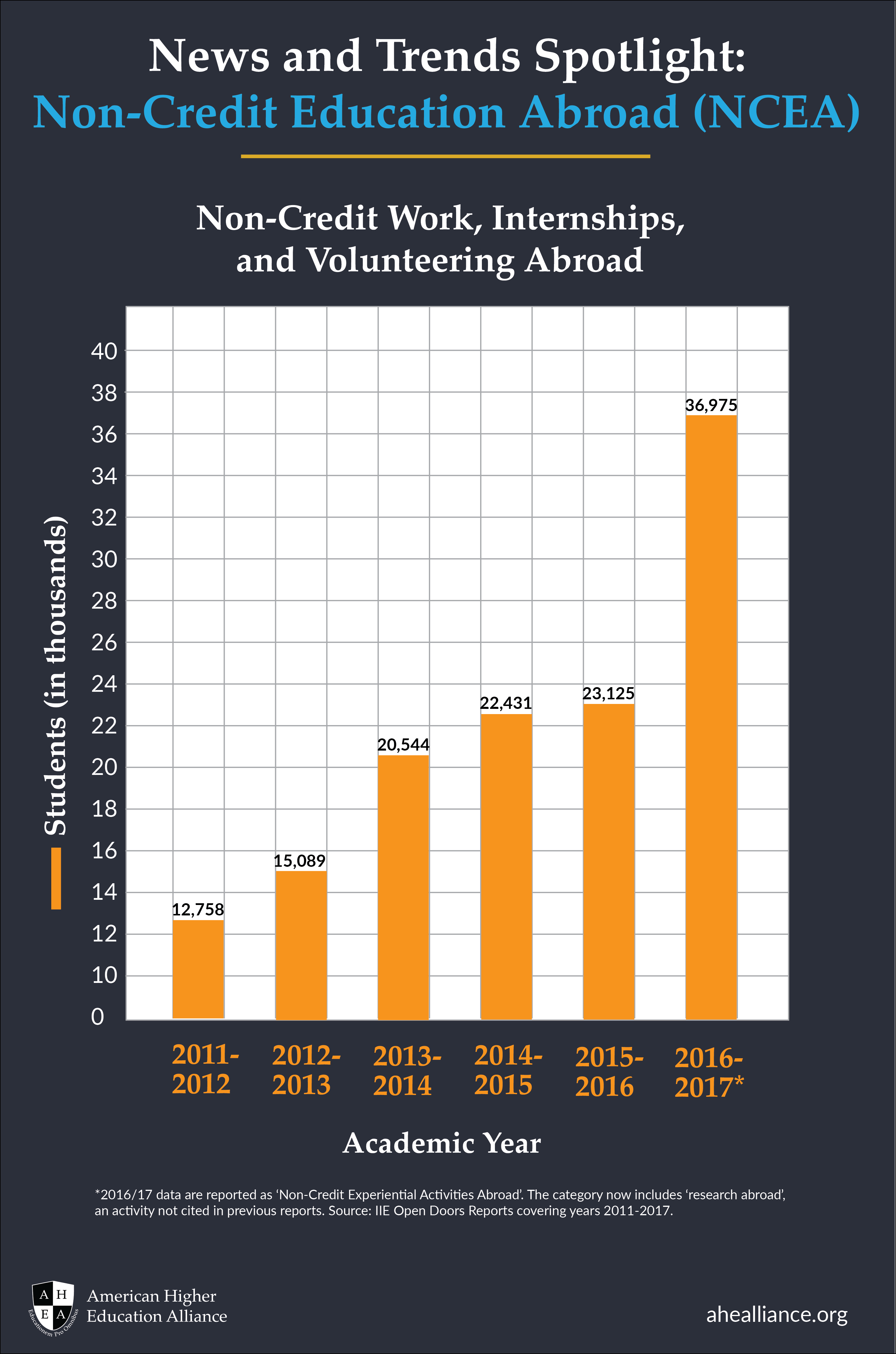

News and Trends Spotlight: Non-Credit Education Abroad

According to the 2018 Open Doors report of the Institute of International Education (IIE), 332,727 American students received academic credit for participation in study abroad programs in 2016/17. The report also states that another 36,975 students ‘participated in non-credit work, internships, volunteering, and research abroad’. This figure, which represents a significant increase over the previous year, may reflect the IIE’s inclusion of ‘research abroad’ in the kinds of non-credit activities covered in the report; however, there are signs that the number of students taking part in non-credit educational experiences abroad (and the number of institutions reporting such activities) has been trending upwards for some time.

If the figures presented here support the general view of an increasing incidence in non-credit activity over recent years, the authors of the IIE’s 2016 study The world is the new classroom: Non-credit education abroad further suggest that ‘this vast landscape of experiential learning, which we are calling “Non-Credit Education Abroad” (NCEA), has so far been underreported and not fully understood.’[1]

These issues are explored in some detail throughout the report (based on survey responses from 227 institutions during the 2012/13 academic year) and in turn help to demonstrate the diverse ways in which institutions across the US identify NCEA activity. For example, ‘the vast majority… (85 percent) consider volunteering or service learning to be an NCEA activity. More than half of the institutions identify the following activities as falling under the non-credit umbrella: internship or work abroad (68 percent); research or field work (67 percent); and travel seminar or study tour (59 percent). More than a third of institutions also indicated that educational-related university activities abroad such as international conferences, language study, athletic activities, and religious missions are recognized as NCEA’.[2] In the case of those institutions which reported an increase in such activity, this was attributed to a variety of factors ‘including the increased availability of NCEA programs offered by home campuses (29 percent), students’ increased desire for international work experience (27 percent), improved institutional tracking processes (27 percent), and the flexibility NCEA offers students to gain international experiences without impacting their studies (26 percent)’.[3]

The interest shown by the IIE in clarifying how many students across the country are engaged in NCEA activities as well as the development of best practice guidelines is shared by other organizations. Those interested in learning more about these issues are for example encouraged to consult the work being done by NAFSA’s Subcommittee on Work, Internships, Volunteering and Research Abroad and, specifically, documents such as Creating an Academic Framework for International Internships, which offers insights on important matters of design and assessment. Additional resources of this kind are available from the Forum on Education Abroad in the form of its recently published (2018) ‘Guidelines for Internships Abroad’ and ‘Guidelines for Community Engagement, Service-Learning, and Volunteer Experiences Abroad’.

[1] Mahmoud, O. & Farrugia, C. (2016). The world is the new classroom: Non-credit education abroad. New York: Institute of International Education, pg. 2.

[2] Ibid, pg. 9.

[3] Ibid, pg. 10.